Living Legend Tries to Make a Living

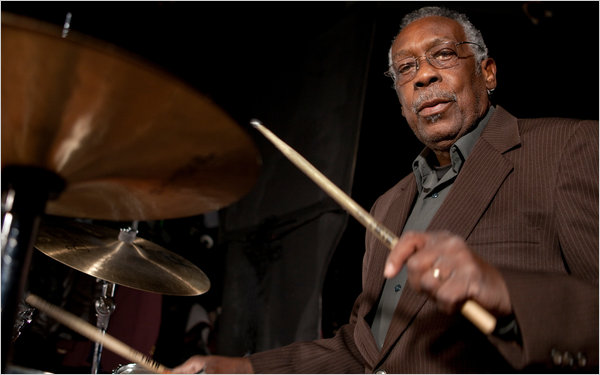

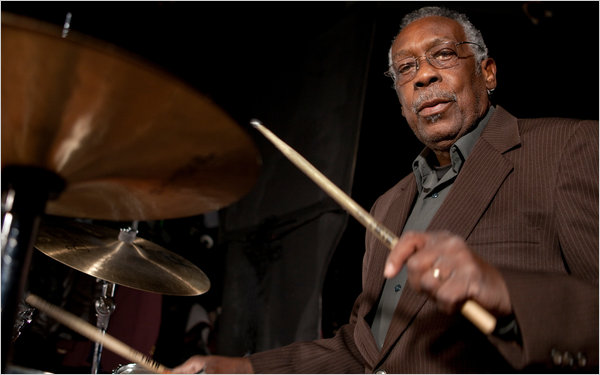

Aside from musicians, record collectors and D.J.’s, the name Clyde Stubblefield does not make many ears perk up. But no matter who you are, you probably know his drumming.

If you’ve heard Public Enemy’s “Bring the Noise” or “Fight the Power,” you know his drumming. If you’ve heard LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out,” or any number of songs by Prince, the Beastie Boys, N.W.A., Run-D.M.C., Sinead O’Connor or even Kenny G., you definitely know his drumming, even though Mr. Stubblefield wasn’t in the studio for the recording of any of them.

That is because he was the featured player on “Funky Drummer,” a 1970 single by James Brown whose 20-second drum solo has become, by most counts, the most sampled of all beats. It’s been used hundreds of times, becoming part of hip-hop’s DNA, and in the late 1980s and early ’90s it was the go-to sample for anyone looking to borrow some of hip-hop’s sass (hence Kenny G.).

Yet Mr. Stubblefield’s name almost fell through the cracks of history. The early rappers almost never gave credit or paid for the sample, and if they did, acknowledgement (and any royalties) went to Brown, who is listed as the songwriter.

“All my life I’ve been wondering about my money,” Mr. Stubblefield, now 67 and still drumming, says with a chuckle.

A new project tries to capture at least some royalties for him. Mr. Stubblefield was interviewed for “Copyright Criminals,” a documentary by Benjamin Franzen and Kembrew McLeod about the gray areas of music copyright law, and for a special “Funky Drummer Edition” DVD of the film released on Tuesday, Mr. Stubblefield recorded a set of ready-to-sample beats. By filling out a basic licensing form, anyone willing to pay royalties of 15 percent on any commercial sales — and give credit — can borrow the sound of one of the architects of modern percussion.

“There have been faster, and there have been stronger, but Clyde Stubblefield has a marksman’s left hand unlike any drummer in the 20th century,” said Ahmir Thompson, a k a Questlove of the Roots, who was to play “Fight the Power” with him and Public Enemy’s Chuck D. on NBC’s “Late Night With Jimmy Fallon” on Tuesday. “It is he who defined funk music.”

Born in Chattanooga, Tenn., Mr. Stubblefield was first inspired by the industrial rhythms of the factories and trains around him, and he got his start playing with regional bands. One day in 1965 Brown saw him at a club in Macon, Ga., and hired him on the spot. Through 1971 Mr. Stubblefield was one of Brown’s principal drummers, and on songs like “Cold Sweat” and “Mother Popcorn” he perfected a light-touch style filled with the off-kilter syncopations sometimes called ghost notes.

“His softest notes defined a generation,” Mr. Thompson added.

“We just played what we wanted to play on a song,” Mr. Stubblefield said in a telephone interview last week, referring to himself and his fellow Brown drummer John Starks, better known as Jabo. (Brown died in 2006.) “We just put down what we think it should be. Nobody directs me.”

You might expect Mr. Stubblefield, who has appeared on some of the greatest drum recordings in history, to have gone on to fame, or at least to a lucrative career playing sessions. But for the last 40 years he has happily remained in Madison, Wis., playing gigs there with his own group and, since the early 1990s, playing on the public radio show “Michael Feldman’s Whad’Ya Know?”

Alan Leeds, whose time as Brown’s tour director overlapped with Mr. Stubblefield’s period in the band, remembers him as a gifted but not terribly ambitious musician. “He was a fun guy,” Mr. Leeds said. “But if one guy was going to be late for the sound check, it was Clyde.”

The technology and conventions of sampling — isolating a musical snippet from one recording and reusing it for another — also kept him from greater recognition. “Funky Drummer” didn’t appear on an album until 1986, when it was on “In the Jungle Groove,” a Brown collection that was heavily picked over by the new generation of sampler-producers.

The lack of recognition has bothered Mr. Stubblefield more than the lack of royalties, he said, although that stings too.

“People use my drum patterns on a lot of these songs,” he said. “They never gave me credit, never paid me. It didn’t bug me or disturb me, but I think it’s disrespectful not to pay people for what they use.”

In 2002 Mr. Stubblefield had a tumor in his kidney removed, and now he suffers from end-stage renal disease. He qualifies for Medicare but has no additional health insurance.

The “Funky Drummer Edition” of “Copyright Criminals” includes Mr. Stubblefield’s beats both on vinyl and as electronic files, and in addition to any licensing, he also gets a small royalty from the DVD, said Mr. McLeod, an associate professor of communications at the University of Iowa. As in his days with Brown, Mr. Stubblefield was also paid a fee for the recording session.

“Breaks” albums with ready-made beats are nothing new in hip-hop. By his reckoning, Mr. Stubblefield has done four or five such collections, but not all of those have paid him his royalties either.

“They sent us royalty papers, but no checks,” he said of one such album made for a Japanese company.

For Mr. Stubblefield, lack of credit is not only an issue with D.J.’s and producers sampling his beats. It was also a bone of contention with Brown, who was famous for running a tight ship — he fined his musicians for missing a beat or having scuffed shoes — and also for not giving his musicians more credit.

“A lot of people should have gotten a lot of credit from James Brown,” Mr. Stubblefield said, “but he only talked about himself. He may call your name on a song or something, but that’s it.”

This raises the question of whether Mr. Stubblefield is himself violating any of Brown’s copyrights by recording beats in the style of those original recordings in Brown’s band. Mr. McLeod dismissed that suggestion, saying that the beats are not identical, and that the original copyright registration forms for Brown’s songs mention melody and lyrics but not rhythm.

And besides, Mr. McLeod added, what you’re getting is simply a great drummer doing his thing.

“This differs from buying a sample pack for GarageBand,” he said, referring to Apple’s home-recording program, “because you know that what you are listening to and what you are sampling is the genius labor of this incredible musician. It’s Clyde Stubblefield.”

Aside from musicians, record collectors and D.J.’s, the name Clyde Stubblefield does not make many ears perk up. But no matter who you are, you probably know his drumming.

If you’ve heard Public Enemy’s “Bring the Noise” or “Fight the Power,” you know his drumming. If you’ve heard LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out,” or any number of songs by Prince, the Beastie Boys, N.W.A., Run-D.M.C., Sinead O’Connor or even Kenny G., you definitely know his drumming, even though Mr. Stubblefield wasn’t in the studio for the recording of any of them.

That is because he was the featured player on “Funky Drummer,” a 1970 single by James Brown whose 20-second drum solo has become, by most counts, the most sampled of all beats. It’s been used hundreds of times, becoming part of hip-hop’s DNA, and in the late 1980s and early ’90s it was the go-to sample for anyone looking to borrow some of hip-hop’s sass (hence Kenny G.).

Yet Mr. Stubblefield’s name almost fell through the cracks of history. The early rappers almost never gave credit or paid for the sample, and if they did, acknowledgement (and any royalties) went to Brown, who is listed as the songwriter.

“All my life I’ve been wondering about my money,” Mr. Stubblefield, now 67 and still drumming, says with a chuckle.

A new project tries to capture at least some royalties for him. Mr. Stubblefield was interviewed for “Copyright Criminals,” a documentary by Benjamin Franzen and Kembrew McLeod about the gray areas of music copyright law, and for a special “Funky Drummer Edition” DVD of the film released on Tuesday, Mr. Stubblefield recorded a set of ready-to-sample beats. By filling out a basic licensing form, anyone willing to pay royalties of 15 percent on any commercial sales — and give credit — can borrow the sound of one of the architects of modern percussion.

“There have been faster, and there have been stronger, but Clyde Stubblefield has a marksman’s left hand unlike any drummer in the 20th century,” said Ahmir Thompson, a k a Questlove of the Roots, who was to play “Fight the Power” with him and Public Enemy’s Chuck D. on NBC’s “Late Night With Jimmy Fallon” on Tuesday. “It is he who defined funk music.”

Born in Chattanooga, Tenn., Mr. Stubblefield was first inspired by the industrial rhythms of the factories and trains around him, and he got his start playing with regional bands. One day in 1965 Brown saw him at a club in Macon, Ga., and hired him on the spot. Through 1971 Mr. Stubblefield was one of Brown’s principal drummers, and on songs like “Cold Sweat” and “Mother Popcorn” he perfected a light-touch style filled with the off-kilter syncopations sometimes called ghost notes.

“His softest notes defined a generation,” Mr. Thompson added.

“We just played what we wanted to play on a song,” Mr. Stubblefield said in a telephone interview last week, referring to himself and his fellow Brown drummer John Starks, better known as Jabo. (Brown died in 2006.) “We just put down what we think it should be. Nobody directs me.”

You might expect Mr. Stubblefield, who has appeared on some of the greatest drum recordings in history, to have gone on to fame, or at least to a lucrative career playing sessions. But for the last 40 years he has happily remained in Madison, Wis., playing gigs there with his own group and, since the early 1990s, playing on the public radio show “Michael Feldman’s Whad’Ya Know?”

Alan Leeds, whose time as Brown’s tour director overlapped with Mr. Stubblefield’s period in the band, remembers him as a gifted but not terribly ambitious musician. “He was a fun guy,” Mr. Leeds said. “But if one guy was going to be late for the sound check, it was Clyde.”

The technology and conventions of sampling — isolating a musical snippet from one recording and reusing it for another — also kept him from greater recognition. “Funky Drummer” didn’t appear on an album until 1986, when it was on “In the Jungle Groove,” a Brown collection that was heavily picked over by the new generation of sampler-producers.

The lack of recognition has bothered Mr. Stubblefield more than the lack of royalties, he said, although that stings too.

“People use my drum patterns on a lot of these songs,” he said. “They never gave me credit, never paid me. It didn’t bug me or disturb me, but I think it’s disrespectful not to pay people for what they use.”

In 2002 Mr. Stubblefield had a tumor in his kidney removed, and now he suffers from end-stage renal disease. He qualifies for Medicare but has no additional health insurance.

The “Funky Drummer Edition” of “Copyright Criminals” includes Mr. Stubblefield’s beats both on vinyl and as electronic files, and in addition to any licensing, he also gets a small royalty from the DVD, said Mr. McLeod, an associate professor of communications at the University of Iowa. As in his days with Brown, Mr. Stubblefield was also paid a fee for the recording session.

“Breaks” albums with ready-made beats are nothing new in hip-hop. By his reckoning, Mr. Stubblefield has done four or five such collections, but not all of those have paid him his royalties either.

“They sent us royalty papers, but no checks,” he said of one such album made for a Japanese company.

For Mr. Stubblefield, lack of credit is not only an issue with D.J.’s and producers sampling his beats. It was also a bone of contention with Brown, who was famous for running a tight ship — he fined his musicians for missing a beat or having scuffed shoes — and also for not giving his musicians more credit.

“A lot of people should have gotten a lot of credit from James Brown,” Mr. Stubblefield said, “but he only talked about himself. He may call your name on a song or something, but that’s it.”

This raises the question of whether Mr. Stubblefield is himself violating any of Brown’s copyrights by recording beats in the style of those original recordings in Brown’s band. Mr. McLeod dismissed that suggestion, saying that the beats are not identical, and that the original copyright registration forms for Brown’s songs mention melody and lyrics but not rhythm.

And besides, Mr. McLeod added, what you’re getting is simply a great drummer doing his thing.

“This differs from buying a sample pack for GarageBand,” he said, referring to Apple’s home-recording program, “because you know that what you are listening to and what you are sampling is the genius labor of this incredible musician. It’s Clyde Stubblefield.”

Home

Home